Beauty, goodness, and truth as needed foundations to catechesis

TIMOTHY P. O’MALLEY

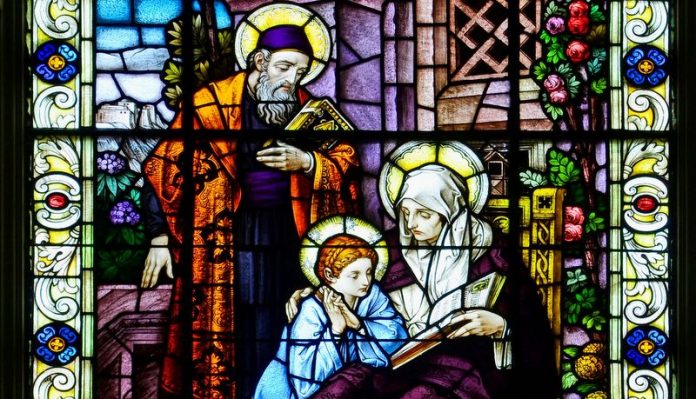

Medieval historiography contends that the function of stained glass was to educate the illiterate. This assertion presumes that the capacity to read eliminates the need for the arts in Christian life. Once women and men can read, aesthetics become a pleasant accessory to solid formation in Christian faith.

This historical claim is false. The medieval aesthetic experience was not reserved for the illiterate. Windows performed sophisticated scriptural catechesis through the medium of stained glass for the literate and illiterate alike. (Want more on this subject? Read The Narratives of Gothic Stained Glass by Wolfgang Kemp, published by Cambridge University Press.)

This historical claim is false. The medieval aesthetic experience was not reserved for the illiterate. Windows performed sophisticated scriptural catechesis through the medium of stained glass for the literate and illiterate alike. (Want more on this subject? Read The Narratives of Gothic Stained Glass by Wolfgang Kemp, published by Cambridge University Press.)

These stained glass windows were important to both the reader and nonreader because such art pointed toward the nature of Christian faith itself. Faith is a moment of divine illumination in which human perception becomes suffused with the gift of grace. We “see” or “hear” with faith-filled senses.

Unfortunately, catechesis today rarely operates out of this same medieval aesthetic. In fact, one might argue it lacks an aesthetic at all. Art has a place. But the primary intention of such aesthetic media is to communicate a truth in a more agreeable manner. Paintings or stained glass windows are meant to “present” a meaning to the contemporary person. Music is appropriated for the way it speaks about God. Students may draw in class, at best, as a way of appropriating the lesson; at worst, as a way to pass some time before parents pick them up.

The goal of this essay is to propose a new foundation for catechesis. Rather than see the aesthetic task as a pleasant, albeit unnecessary, diversion, what if aesthetic formation was the foundation of all catechesis? How would this change how we catechists go about our art?

The beauty of Jesus Christ

The theologian Hans urs von Balthasar is important to this conversation. Von Balthasar has written a multivolume work on theological aesthetics entitled The Glory of the Lord. In this work, von Balthasar describes how the aesthetic is essential to any act of theology. Here, he does not mean that the theologian must analyze pieces of art. Instead, theology is aesthetic because it pertains to the perception of a concrete form, the person of Jesus Christ, who is the Word made flesh. He writes:

The theologian Hans urs von Balthasar is important to this conversation. Von Balthasar has written a multivolume work on theological aesthetics entitled The Glory of the Lord. In this work, von Balthasar describes how the aesthetic is essential to any act of theology. Here, he does not mean that the theologian must analyze pieces of art. Instead, theology is aesthetic because it pertains to the perception of a concrete form, the person of Jesus Christ, who is the Word made flesh. He writes:

… man is not merely addressed in a total mystery, as if he were compelled to accept obediently in blind and naked faith something hidden from him, but that something is “offered” to man by God, indeed offered in such a way that man can see it, understand it, make it his own, and live from it in keeping with his human nature. [See Hans urs von Balthasar, The Glory of the Lord: A Theological Aesthetics — Volume I: Seeing the Form, trans. Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1982), 121. ]

What we see in Jesus Christ is more than a cult of the pretty. Instead, it’s the revelation that total and absolute Love has come to dwell among us through the incarnation of the Word. Jesus Christ, the one who sups with sinners, preaches the kingdom of God, dies on the cross, and is raised on the third day, is the very form of this absolute, divine Love.

Thus, in the person of Jesus Christ, we see two dimensions of beauty important to medieval thought. First, there is the concrete form that any object takes. For instance, a vase has a specific form or figure that we encounter. This form is part of what makes a vase beautiful — just ask a novice pottery student about the difficulty of developing a beautiful form. Second, there is the splendor that is made manifest through the form. I’ll always remember the first time I stood before George Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” at the Art Institute of Chicago. The form of Seurat’s pointillism was immediately evident on the large canvas. But the event of encountering the painting was not reducible to the form. Instead, the form manifested to me a splendor, a beauty, a wonder that only this painting could present. The painting didn’t tell me about the meteorological condition of a Sunday afternoon on a Parisian island. Instead, it allowed me to encounter this island, to perceive for a moment its splendor.

Thus, in the person of Jesus Christ, we see two dimensions of beauty important to medieval thought. First, there is the concrete form that any object takes. For instance, a vase has a specific form or figure that we encounter. This form is part of what makes a vase beautiful — just ask a novice pottery student about the difficulty of developing a beautiful form. Second, there is the splendor that is made manifest through the form. I’ll always remember the first time I stood before George Seurat’s “A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte” at the Art Institute of Chicago. The form of Seurat’s pointillism was immediately evident on the large canvas. But the event of encountering the painting was not reducible to the form. Instead, the form manifested to me a splendor, a beauty, a wonder that only this painting could present. The painting didn’t tell me about the meteorological condition of a Sunday afternoon on a Parisian island. Instead, it allowed me to encounter this island, to perceive for a moment its splendor.

In Jesus Christ, form and splendor reach their zenith. Through the form of Jesus Christ, the Godman, it is the glory of the Lord that we perceive. Catholicism does not presume that we must simply believe this to be true, to jump into the naked abyss where all we have is faith in this proclamation. Instead, Catholicism believes that this form is mediated to us through the Scriptures, the sacraments, the Church’s kerygma and doctrine, and the saints. The Christian must learn to contemplate this form, a process that von Balthasar calls attunement. By entering into an apprenticeship of contemplating the form of Jesus Christ as mediated by the Church, we gradually learn to see the world in light of the splendor of God.

Of course, this process is not dependent on human effort but is always a gift from God. It is

grace, Christ working within the life of the Christian, that brings about this attunement. But God, perhaps foolishly from our perspective, has decided to save humanity through that which is most human. Beauty, within Catholicism, is thus not an accessory to either goodness or truth. We can’t debate what it means to live a “good life” in Catholicism without first perceiving the form of this life in Jesus Christ. We can’t talk about the truth of a dogma or a particular moral teaching until we first “see” the truth and splendor of Jesus in its entirety. In the latter instance, truth would be reduced to facts rather than a perception of God’s own salvific love for the human person. Beauty thus must lead the way in catechesis, because catechesis is intended for human beings learning to become divine.

A beautiful catechesis

If von Balthasar is right, then catechesis must start out from aesthetics or the science of the beautiful. It must be an education of our imaginations to recognize the splendor of what is revealed in the person of Jesus Christ. Catechesis may approach this renewal in the following three ways:

1 The beauty of textbooks: The first task of catechesis must be to perform an aesthetic audit of textbooks. Here, I do not mean that we need to make sure that textbooks contain sufficient classical art or beautiful graphic design. The aesthete may love art but not believe in its truth. Beauty must always be at the service of revealing the God who shows us what it means to be beautiful: Jesus Christ. The assessment will thus proceed through attention to both form and splendor. Do the textbooks sufficiently reveal the glorious form of the Word made flesh, the splendor of the Father? Do they attend to the beauty of a God who emptied himself in total, self-giving love? Is the language of the textbook didactic or doxological? Does it employ the prayerful discourse of the mystics instead of deadening prose? Does it introduce the historical “forms” that have mediated this encounter with Jesus Christ, or does it rely more on the movement of the affections alone?

2 The explicit aesthetic curriculum: Part of the assessment will necessarily involve attention to art. Christian art is not decoration used to demonstrate a point. Christian art possesses its own pedagogy insofar as such art is one of the forms that God uses for the education of our spiritual senses.

Yet many catechetical curricula reveal that explicit formation into the history of Christian art is entirely absent. Students in catechesis may learn nothing about baptisteries, chant and polyphony, the role of sculpture, stained glass, devotional poetry, Catholic hymnody, and altarpieces. My university undergraduates often can’t name a single Catholic artist, musician, or poet.

If beauty is essential to discovering Jesus Christ, then a catechetical curriculum that seeks to facilitate an encounter with Jesus will employ the material and aesthetic tradition of the Church in preparing the human being for this meeting.

3 The implicit aesthetic curriculum: Textbooks and curricula are not the only facets of the Church’s catechesis. Instead, we have to recognize that the implicit curriculum of our parishes is often ugly. Ugly preaching, architecture, music, liturgy, art, and literature fill our parishes. Such art is ugly not simply because it isn’t quaint or pretty. After all, the cross is the center of Christian beauty — and what could be less aesthetically pleasing than the death of God on the cross? Instead, it is “ugly” because it fails to point to the splendor of a God who is total, absolute Love.

It’s ugly because it tries too hard to “proclaim” a message constructed by human beings instead of facilitating a contemplative encounter with the Word made flesh.

And isn’t that encounter what catechists really hope for in the first place?

Timothy P. O’Malley, Ph.D., is the director of the Notre Dame Center for Liturgy at the McGrath Institute for Church Life. He is the author of Bored Again Catholic: How the Mass Could Save Your Life (Our Sunday Visitor, 2017).

The article was originally published in Catechist magazine, April 2019

PHOTOS (T-B): BAUHAUS1000/ISTOCK, MANJIK/ISTOCK, CRISFOTOLUX/ISTOCK, RUDIMENCIAL/ISTOCK