By Timothy P. O’Malley

Catechists have often heard the complaint that the Mass is boring. Children and teens express their boredom directly through yawns or by demanding a more engaging liturgical experience. Boredom, for adults, is more subtle — signified by glassy eyes during the homily, the Eucharistic Prayer, and the closing announcements.

Such boredom is not only found in those who are mildly engaged in Catholic practice. We all, at some point in our journey of faith, have discovered that we are going through the motions. Favorite hymns become something to get through as quickly as possible. We find ourselves absentmindedly eating and drinking Christ’s Body and Blood even though the Eucharist is the very love of God made present among us.

The problem of being bored at Mass can become an invitation for liturgical catechists to reconsider how to teach people the art of prayer through a renewed liturgical catechesis. Catechesis on the Mass for the bored should be:

- Full of wonder

- Centered on the kerygma

- Linked closely to spiritual practice

If such catechesis becomes central to the life of the Church, then boredom will become an opportunity for renewal rather than an obstacle we must contend with.

A wonder-filled catechesis

There is a tendency, perhaps well-intentioned, to blame modern technology for boredom. Kids and adults alike are bored during Mass because they have become addicted to the digital world. Undoubtedly, the growth of technology has affected our capacity to pray, to dwell in silence before the living God. But we must be honest with ourselves: Sometimes we are bored at Mass because we have done everything possible to make Mass boring. This kind of boredom must be eliminated if we are to teach people to pray the Mass.

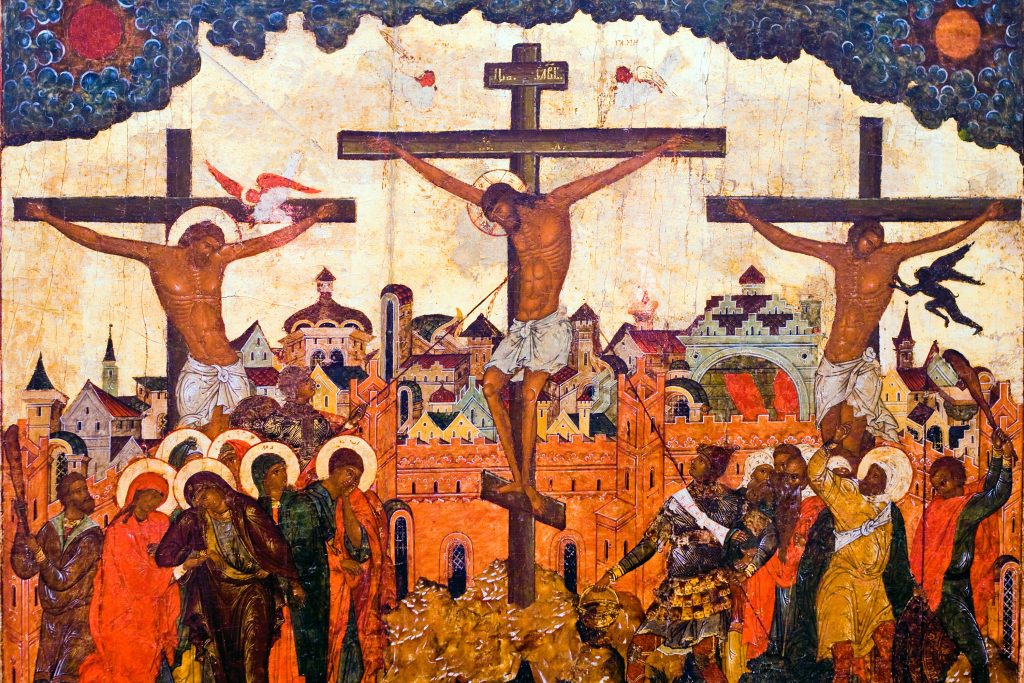

The celebration of the Mass takes place through wonderful signs. Church buildings capture the imagination through sacred images that show how every dimension of human life and culture has been transformed through the Gospel. Music during the celebration of the Eucharist leads Mass-goers to delight in praising the living God, uniting all their senses to the liturgy of heaven itself. The voice of the celebrant, taken up in prayer, is a sign that moves the assembly toward contemplating the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Of course, this is ideally how the Mass ought to treat sacred signs. In reality our church buildings can look more like suburban shopping malls, absent of any reference to sacred history or local culture. Music during Mass risks becoming the delight of aesthetes (who like good art), remnants of popular music during whatever age our hymnal was assembled, or an assault upon the ears by an untrained choir. The public proclamation of the prayers of the Mass often are indistinguishable from what it might sound like if the priest read the phone book aloud.

When we treat the Mass in this way, we perform an act of anti-catechesis that eliminates wonder — which is the beginning of philosophy, the pursuit of wisdom as a form of life. Wonder is not simply awe before some amazing object. Rather, it is an encounter that leads us to long for more, to ask questions. Wonder precipitates a reservoir of desire.

As the great catechist Sofia Cavalletti, wrote, “Wonder will be quenched if it does not find a worthy object, if it lingers on limited objects; such objects will inevitably disappoint the child.” The first step to eliminate boredom must involve catechesis that invites a renewal of the “wonderful” signs of the Mass itself. We must ask ourselves if our spaces for worship are images of the cosmic transformation of creation that has taken place through Jesus Christ. We must discern if our music invites people to encounter the Word made flesh, the splendor of the Father. We must address preaching that stultifies rather than leads people to long for a deeper encounter with the risen Lord. We must develop an approach to prayer that leads to silence before the tremendous glory of God. We must use light and darkness, incense and candles, stained glass windows and statues that represent the salvation of the human body itself.

In Christian worship, signs matter. And catechesis on the Mass must begin with a renewal of the signs themselves. Liturgy and catechesis need more wonderful signs to contemplate.

The centrality of the kerygma

Another major cause of boredom is a failure to understand the “mystery” that the celebration of the Mass points toward. For many Americans, religion is fundamentally about having a benign ethical stance toward the world. Religion helps us to be nice, decent, good people, who (God-willing) will enter heaven. The Mass is helpful insofar as it teaches us to be such generally good people.

Of course, this is not how the Church has understood the celebration of the Mass throughout her history. Going to Mass is about letting our stories, our narratives, our histories be transformed through the great story of salvation revealed in the presence of Christ. Like the disciples on the road to Emmaus in the Gospel of Luke, we hear the words of the risen Lord explaining to us the meaning of the salvation promised in the Scriptures. We then kneel before the altar in the breaking of the bread, learning to see Christ’s presence dwelling among us. We eat his Body and drink his Blood, and in the process, we are transformed into living signs of love for the world.

The Mass is not first and foremost about ritual or ethical behavior. It is a participation in what the Father has accomplished through Christ. It is the Spirit breathing anew among us.

For this reason, if we want to move people from boredom to wonder, it is necessary that we begin with the kerygma, the story of salvation at the heart of the Eucharist. This kerygma reveals to us that God is love, wanting to share in communion with all of creation (including us!). As Benedict XVI wrote in his apostolic exhortation The Sacrament of Charity: “In the bread and wine under whose appearances Christ gives himself to us in the paschal meal (cf. Luke 22:14-20; 1 Corinthians 11:23-26), God’s whole life encounters us and is sacramentally shared with us.” Every moment of the Mass prepares men and women for this sublime communion with God. When we hear the opening prayer at Christmas, we contemplate what it means for humanity and divinity to be united in Christ. When we sing the sequence on Easter Sunday, we join Mary Magdalene in encountering the risen Lord. When we listen to Eucharistic Prayer II, calling the Spirit to descend upon the gifts like the dewfall, we remember the gift of manna in the desert and become pilgrims longing for the bread of life. And during the Eucharistic Prayer, as we ask the Church to experience the communion of love made possible by the Eucharist, we become God’s total love for the life of the world.

If Catholics continue to see the Mass as part of the ethics of religion, then they will continue to be really, really bored. The Mass is salvation history unfolding here and now. And that means that we have to know that history to really celebrate the Mass well.

The gift of spiritual practice

If you sat me down at a piano, I would find it immensely boring. Not because I don’t like listening to the piano, but because I don’t know how to play it. I would fumble around, making some broadly recognizable chords. I would find middle C and play scales. But quickly I would tire of my inept piano playing and move on.

One of the reasons that Catholics are bored at Mass is because liturgical catechesis, while often explaining what the Mass means, often neglects to focus on teaching people to actually pray. We learn to pray the Mass by practicing the art of prayer.

In this sense, spiritual practice is essential to a renewed liturgical catechesis for the Mass. We cannot expect people to delight again and again in the words of the Eucharistic Prayer if they don’t spend time on their own meditating on the words of the Scriptures. We cannot expect people to delight in kneeling in Mass if they never kneel on their own in private prayer. We cannot hope that people will hunger and thirst for the Bread of Life if they don’t spend some time fasting. We cannot suppose that the assembly will find silence fruitful in their lives if they are never silent on their own.

We are embodied creatures, and every spiritual practice we form helps us grow in the spiritual life. If we are bored at Mass, it’s because we may not be aware that we are being invited more deeply into prayer with God — to discover a deeper relationship with God in our lives. The Mass can’t do everything, and for that reason we need to promote robust spiritual practices throughout life that form a person for the art of prayer.

In this sense, our goal as catechists is not to explain the Mass one more time, as if a didactic approach will heal someone’s boredom. Our goal as catechists is to teach people to enter into the silence, to lift up their hearts to God, and to offer that sacrifice of praise not simply during the Mass but during every moment of the day.

Then, when we find ourselves bored at Mass, we will enter more deeply into prayer rather than turning to our smartphones, looking for something more engaging.

We know that the problem isn’t the Mass. It’s us.

Timothy P. O’Malley, Ph.D., is director of the Notre Dame Center for Liturgy at the McGrath Institute for Church Life. He is the author of Bored Again Catholic: How the Mass Could Save Your Life (Our Sunday Visitor, 2017).

Image credits: Vibrant Image Studio/Shutterstock; Thoai/Shutterstock.