Reflecting, acting, and praying with mercy

JARED DEES

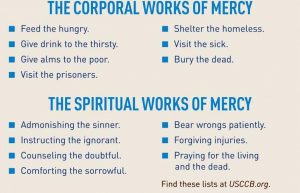

Jesus said, “Go and learn the meaning of the words, ‘I desire mercy, not sacrifice’” (Matthew 9:13). Many of us — myself included — sometimes feel guilty about not doing more works of mercy. These works, however, should come from a source of charity, not obligatory sacrifice. As the Catechism says, “The works of mercy are charitable actions by which we come to the aid of our neighbor in his spiritual and bodily necessities” (CCC, 2447).

In the Parable of the Good Samaritan, the scholar of the law asked Jesus: “And who is

my neighbor?” (Luke 10:29). A neighbor is anyone who, like the Good Samaritan, treats others with mercy. Here are a few ways we can give students the experience of this mercy without leaving the classroom:

1. Meditate on the works of mercy If we want our students to do the works of mercy out of a sense of charity rather than obligation, then we must give them the chance to personalize them. To meditate on something from a Christian point of view means to make connections between a teaching and one’s personal life experiences.

1. Meditate on the works of mercy If we want our students to do the works of mercy out of a sense of charity rather than obligation, then we must give them the chance to personalize them. To meditate on something from a Christian point of view means to make connections between a teaching and one’s personal life experiences.

Introduce students to a work of mercy and ask them how they have been the recipient of it. Ask them how they have seen others perform each work of mercy. Ask them how they have practiced the works of mercy in their own lives. You could even ask them how they have failed to practice each work of mercy.

The key to these or any question you might ask as a form of meditation is to invite students themselves to make those essential, personal connections. The goal is to help them reflect on ways they have experienced the works of mercy and are called to practice them.

2. Skits and scenarios One of the best ways to personalize and add meaning to Church teachings is to have students act out skits or scenarios that show how someone can apply these ideas. For the works of mercy, assign each one of the works to individual groups of a few students each. Give them time to plan a skit that shows that work of mercy in action, and then have them act it out in front of the class. You might even suggest that they perform two skits: one with a person doing the work of mercy and one with them failing to practice mercy. Make sure you discuss each skit afterward, and then continue to challenge the students to make personal connections with ways they can live out each scenario in their own daily lives.

3. Praying the works of mercy Turn each one of the works of mercy into an opportunity to create prayers. Students can compose prayers asking forgiveness for the specific times they did not practice the works of mercy when they had the opportunity to do so. More importantly, though, praying guides them to feel mercy for specific people. Have them pray for the hungry, thirsty, naked, homeless, sick, imprisoned, and the dead. Have them pray for those who are doubtful, ignorant, sinners, or sorrowful. Have them pray for those who have offended them. These prayers, especially when said out loud or written out, can be powerful ways for the students to experience a sense of mercy. Imagine what might happen next: Instead of performing each of these works of mercy out of a sense of duty, they will do so out of a sense of the true mercy they felt through prayer.

4. Assigned and unassigned homework Finally, think about the works of mercy as opportunities for assigned and unassigned homework. Assign one of the corporal or spiritual works of mercy as an obligatory homework assignment and tell students to write in a journal about the experience. You could also share stories of your own experience practicing the works of mercy and then invite them to do the same in their lives. If mercy is something that is truly important to you, check in with them every time you see them and ask who performed a work of mercy since you last saw them. The more you ask, the more accountability they will feel and the more they will look for opportunities to practice mercy in their daily lives.

Jared Dees is the founder of TheReligionTeacher.com and the author of Christ in the Classroom, which applies the practice of lectio divina to lesson planning.

This article was originally published in Catechist magazine, October 2019

PHOTO: SERGEY NOVIKOV/SHUTTERSTOCK