Using Aristotelian concepts as a teaching method

AARON T. MARTIN

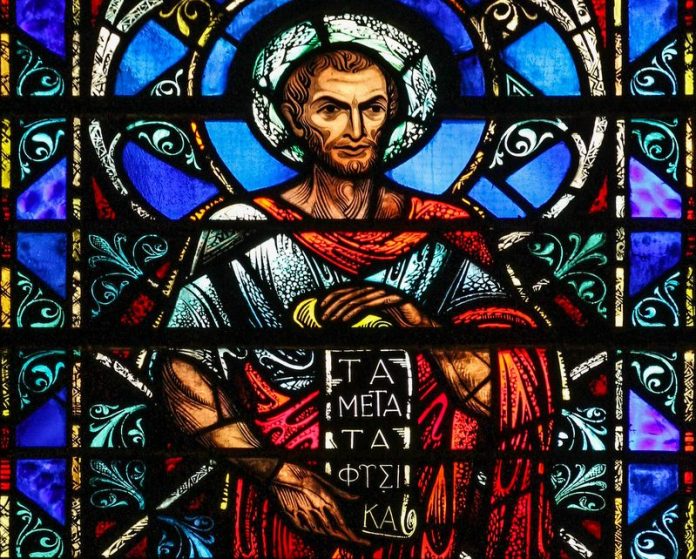

One of the most beautiful churches in the country stands at Lexington Avenue and 66th Street in New York City. St. Vincent Ferrer is beautiful for many reasons, including the communion of saints depicted in its stained glass windows. And there, among the many gold halos, is a conspicuously green halo around the head of the pagan philosopher, Aristotle (384–322 BC). Aristotle has been recognized throughout the centuries as a foundational influence on the Church, which is why he has stood beneath St. Albert the Great and across the nave from St. Thomas Aquinas at St. Vincent Ferrer Church for the last 100 years.

You probably use Aristotelian concepts all the time without even realizing it. Try to explain transubstantiation without using the concepts of “substance” and “accident.” Or think of how you explained “consubstantial” when the translation of the Creed changed a few years ago. We may not use Aristotle’s exact terms, but we certainly use his concepts (see CCC, 251).

You probably use Aristotelian concepts all the time without even realizing it. Try to explain transubstantiation without using the concepts of “substance” and “accident.” Or think of how you explained “consubstantial” when the translation of the Creed changed a few years ago. We may not use Aristotle’s exact terms, but we certainly use his concepts (see CCC, 251).

Aristotle was a practical philosopher. He began by looking around him, seeing how things worked, seeing how people and animals behaved, and making conclusions about the nature of things from those observations. In catechesis, we use a similar process, starting from what is most familiar to lead us to the divine. “Since our knowledge of God is limited, our language about him is equally so. We can name God only by taking creatures as our starting point, and in accordance with our limited human ways of knowing and thinking” (CCC, 40). And today, perhaps more than ever, Aristotle is a great help in explaining the principles of the faith.

Many of Aristotle’s ideas were incorporated into Church teaching centuries ago. We ought to make them more explicit in our catechesis today because they help explain the principles of the faith on a deeper level. That’s why “the Church considers philosophy an indispensable help for a deeper understanding of faith and for communicating the truth of the Gospel to those who do not yet know it” (Fides et Ratio, 5).

Among the many Aristotelian concepts we could choose, consider how you might use these:

THE FOUR CAUSES

Being able to explain the efficient, material, formal, and final causes of things helps to inform a variety of teachings, from God’s work in creation and the human soul to the dignity of the person and our search for God and our desire for heaven.

HYLOMORPHISM

Aristotle believed that all things have matter (the “stuff ” they are made of) and a form (the “animating principle”). For humans, that is our body and soul. One great application and expansion of this concept is found in John Paul II’s theology of the body, where he explains how the body is an outward manifestation or reflection of the soul.

SUBSTANCE AND ACCIDENT

You just can’t explain some things, such as the Eucharist, without explaining what substance and accident are (see CCC, 1376).

These philosophical concepts add precision and clarity to our discussions. In my experience

teaching adults, these concepts give my students a deeper understanding. Here’s but one example, using Aristotle’s idea of habit.

Aristotle believes that humans have an abiding and distinctive human nature that leads them to act in a distinctively “human” way. At the same time, Aristotle recognized that people change in certain ways throughout life. A person can become more or less patient, more or less brave, more or less prudent. These changes come about through repeated action in the pursuit of a perceived good. Those actions, in turn, create habits, which then become virtues or vices. (Even when people sin, they are still pursuing something they consider to be “good,” although it is distorted.)

For example, you may decide to give money to someone on the side of the road one week. You may give a larger-than-average tip to a waitress the next week. Then you may decide to volunteer at a homeless shelter. Each of these individual acts of generosity helps you develop a habit of generosity. And once generosity becomes a habit, it becomes easier to do. Eventually, acting generously time after time turns into a virtue that, at least in part, defines you as a person. The “generous person” performs generous acts naturally — easily, readily, and with pleasure.

But the opposite may also be true. How many times have you gone to confession and confessed the same sins as your previous confession, or even the last several confessions? That is an example of habitual sin. And those bad habits — those sins — developed because of individual actions and choices. Telling one lie does not make you a “liar.” It’s not natural yet. But the more individual lies you tell, the more it becomes a habit. Being a “liar” then starts to define who you are. It is your default action because you have the vice of lying — something you also do easily, readily, and with pleasure (or at least without remorse).

Now, apply that concept to explain virtue and sin in the Christian moral life, and certain things stand out. We end the Act of Contrition resolving to “avoid the near occasion of sin,” recognizing that every habitual sin begins in a small way. And Aristotle’s concept of habit also helps explain why frequent confession is an indispensable aid to a virtuous life. On a natural level, we can understand how individual acts shape who we are. On the supernatural level, we can clarify how even small acts have eternal consequences and explain how grace can help us make different choices.

A priest once suggested to me that every theological problem is, at its heart, a philosophical problem. He meant that when we get basic concepts such as substance and essence wrong, it’s hard to explain theological concepts such as the Trinity or transubstantiation correctly. Aristotle gives us many basic principles that we can use to prepare people for deep catechesis. Great theologians and saints through the ages have used Aristotle’s principles. We would do well to follow their example.

Aaron T.Martin, JD, PhL, is an attorney in Phoenix, Arizona. He received his bachelor and licentiate degrees in philosophy from the Catholic University of America. He is an instructor for the Kino Catechetical Institute for the Diocese of Phoenix.

This article was originally published in Catechist magazine, April 2019.

PHOTO: FR. LAWRENCE LEW, O.P