BY TIMOTHY P. O’MALLEY

The second task of catechesis — liturgical education

All catechesis should be liturgical. Such a claim may generate immediate (and possibly negative) reaction from the reader. After all, the six tasks of catechesis include promoting knowledge of the faith, liturgical education, formation into the moral life, teaching the art of prayer, educating for communal life, and promoting a missionary spirit (see General Directory for Catechesis, 85-86). Liturgical catechesis is but one dimension of studying the mystery of Christ, putting “people not only in touch but in communion, intimacy with Jesus Christ” (John Paul II, Catechesi Tradendae, 5).

This objection would be correct if the liturgical orientation of catechesis was understood merely as related to teaching about the liturgy. But, as I’ll discuss, the liturgical orientation of catechesis pertains to the ultimate goal of catechesis in the work of evangelization. That is, catechesis seeks to form the Christian in the art of self-giving love in every dimension of life. Indeed, the ministry of catechesis should make it possible for the Christian to understand life itself as a worthy sacrifice of praise to the triune God. As Pope Benedict XVI writes in his Sacramentum caritatis (“Sacrament of Charity”): “Worship pleasing to God … becomes a new way of living our whole life, each particular moment of which is lifted up, since it is lived as part of a relationship with Christ and as an offering to God” (71).

The future of catechesis must tread a liturgical path, forming disciples in both contemplating the gift of divine love revealed in Christ and simultaneously offering the return-gift of one’s entire self. Such an approach to catechesis, I suggest, will look specifically to the work of Sofia Cavalletti, and the Catechesis of the Good Shepherd, as a model for reconceiving catechesis as a liturgical task.

Toward liturgical orientation

Allow me to cite the work of Reformed philosopher and theologian, James K.A. Smith. He has invited Protestants, Catholics, and Orthodox alike to attend to the liturgical orientation of all catechesis. For Smith, culture is passed on not through abstract ideas but embodied practices (what he calls “cultural liturgies”). We learn to function as consumers not through reading a series of tomes that lay out the principles of consumer theory. One can even reject consumerism as a lifestyle at an intellectual level and still struggle with the temptations of consumerism.

If Christian formation is to work, according to Smith, it requires a liturgical reorientation of all practices of education, including (and especially) catechesis. It’s not that Christian liturgy passes on a series of abstract doctrines in an engaging way. Instead, as we pray liturgically we learn new bodily habits, new ways of being, that change us into new kinds of human beings. We receive new insights into life, and our imagination is renewed as we worship.

Ask someone who has walked the Camino, participated in Las Posadas, or celebrated the Triduum at a local parish. The formation that has taken place in these ritual acts, in these embodied encounters, is not first and foremost cognitive. One may not even be able to reflect immediately upon the meaning of the event. Rather, in each of these liturgical practices, one has an identity written upon the body. One becomes a pilgrim. One enters into the story of the Holy Family. One participates in the mystery of Christ Jesus, allowing every dimension of our lives to be marked by Jesus’ death and resurrection.

Catechesis, for Smith, must be liturgical because it is only through the act of worship that we learn the new story of divine love. Christian life must be oriented first to an act of reception, an openness to becoming, before we can act. Being paves the way for doing.

Restoring a liturgical approach to catechesis:

an example in Catechesis of the Good Shepherd

If we are to discover anew the liturgical orientation of catechesis, we need to be aware that too much can be ascribed to liturgical practice itself. We need a form of catechesis that emphasizes being before doing, contemplation before action.

The Catechesis of the Good Shepherd (CGS), developed by Sofia Cavalletti (1917-2011), offers the possibility for restoring a liturgical approach to catechesis as a whole. Using a Montessori approach to education, CGS allows the child to contemplate and participate in the mystery of salvation within the atrium (or class, or group, or family setting) and gradually within life itself. This approach to catechesis has adopted the divine pedagogy. It begins from the divine covenant, contemplating the mystery of love revealed in the Scriptures, and then invites children to make a return offering of self both through private and public prayer. The child comes to insights in the silence of the heart that no catechist could reveal, for the child is involved in an intimate and sacramental encounter with Jesus Christ.

While this approach to catechesis is generally reserved to children aged three through 12, there are three principles one might adopt for restoring a liturgical orientation to every act of catechesis.

[The article continues below.]

Begin with the Scriptural encounter

Catechesis is never about learning a religious tradition. It is always an encounter with Jesus Christ that involves every dimension of the human person. In this sense, we should never grow tired of forming disciples in contemplating the mystery of love revealed in the Scriptures. Examples abound: The student learning about the sacrament of marriage discovers first the mystery of love revealed in the wedding at Cana; the group serving the poor in Appalachia contemplate the Good Samaritan in the Gospel of Luke; those struggling to deal with the death of a spouse pray together psalms of lament, asking God to act here and now.

The encounter with the Scriptures is not meant to function merely as an introduction to a lesson. Instead, it is always an opportunity to pray, to proclaim the Good News that God is active here and now. The catechist will, of course, guide the student in the reading of the Scriptures. But if significant time is not spent contemplating the mystery of love revealed in Christ, we should not be surprised if students reject such love.

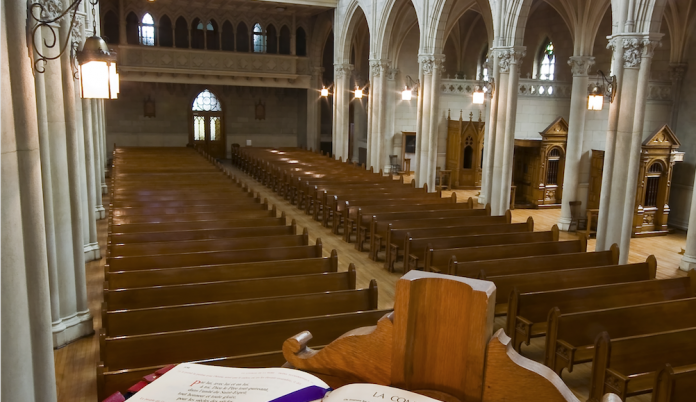

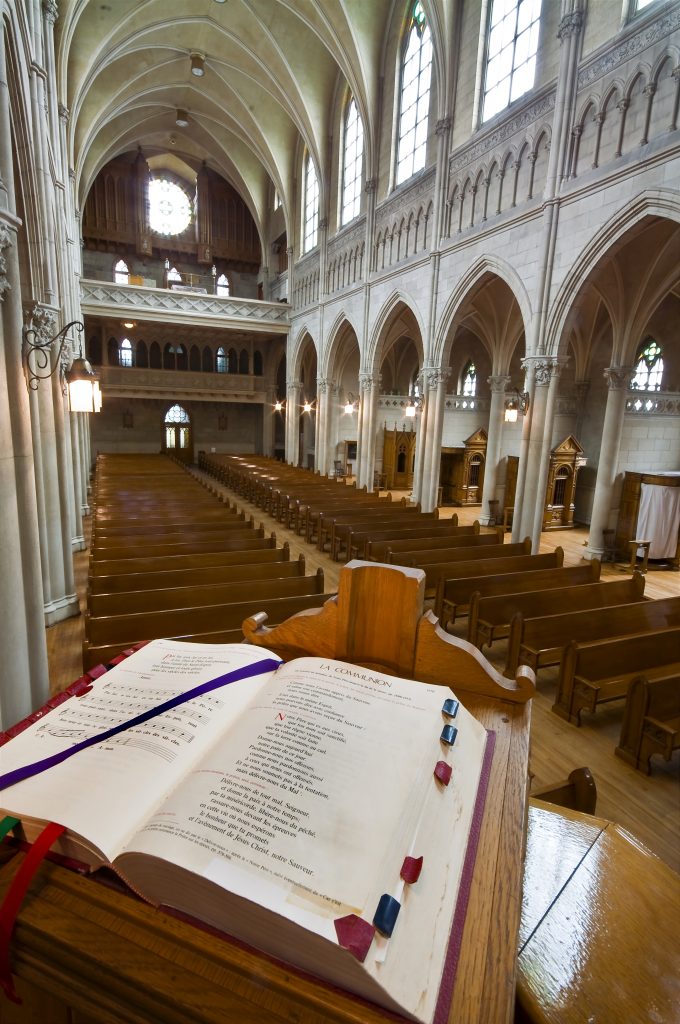

Let liturgy form the body

In the atrium, students kneel. They light candles. They pour water into cruets contemplatively.

It is essential to all catechesis that it include embodied practice grounded in the liturgy. For example, we should pause regularly in our work to bid those being catechized into Eucharistic adoration. We should adapt the Liturgy of the Hours for domestic practice, teaching our families to kiss icons and chant hymns of praise. We should do parish-wide catechesis — not merely in stuffy basements with recorded videos of nationally renowned speakers, but by praying together in churches where there is singing and preaching alike.

Our bodies are being formed through a variety of practices discernable in the world (whether we acknowledge it or not). Restoring a liturgical orientation to catechesis means being intentional about Catholicism’s wisdom regarding liturgical, embodied formation.

See human action as liturgical gift

Catechesis of the Good Shepherd carefully avoids exhorting students to ethical activity apart from an encounter with the covenant of divine love. Christian catechesis is not fundamentally about teaching people to be more just (even if justice is involved). Rather, catechesis forms us to respond with love to the gift of love that we have first received.

This is important in our own age! Young people will not avoid premarital sex because they trust the Church’s guidance. But they will do so if they see human sexuality as linked very closely to the sacrament of marriage, as an offering of love to the God who first loved us. Many will want to be just, to care for the lost and lonely in our world. But they don’t need to see these at odds with worship.

After all, every dimension of human life can become an act of worship for the Christian. And catechesis must form us to renew our imaginations to see every moment of our lives as part of a sacrifice of love. This is how the gap is bridged between liturgy and life.

Conclusion

Restoring the liturgical orientation of catechesis does not mean that every act of catechesis pertains to the liturgy. Rather, it means that the pedagogical wisdom of the liturgy should inspire every dimension of catechesis. This is a wisdom that attends to the encounter of the person with Jesus Christ as mediated through the Scriptures, through the liturgy. It is a wisdom that emphasizes being before doing. It is a wisdom that gradually attunes a person over a lifetime to offer their body as a living sacrifice of love.

Catechesis is necessarily and always liturgical. Even when it’s not teaching about the liturgy.

Timothy P. O’Malley, Ph.D., is director of the Notre Dame Center for Liturgy at the McGrath Institute for Church Life. He is the author of Bored Again Catholic: How the Mass Could Save Your Life (Our Sunday Visitor, 2017).

This article was originally published in Catechist magazine, November/December 2017.

Image credit: F Lariviere / Shutter Stock 78204433